Really Good Schools: Global Lessons for High-Caliber, Low-Cost Education

Really Good Schools: Global Lessons for High-Caliber, Low-Cost Education

By James N. Tooley

Independent Institute, 2021, $29.95; 273 pages.

As reviewed by Paul E. Peterson

Nuggets of amber occasionally reward patient beachcombers who wade through miles of cold, gray clay on the southern shores of the Baltic Sea. Nuggets likewise await the patient reader who wades through this dense, repetitive private-school apology.

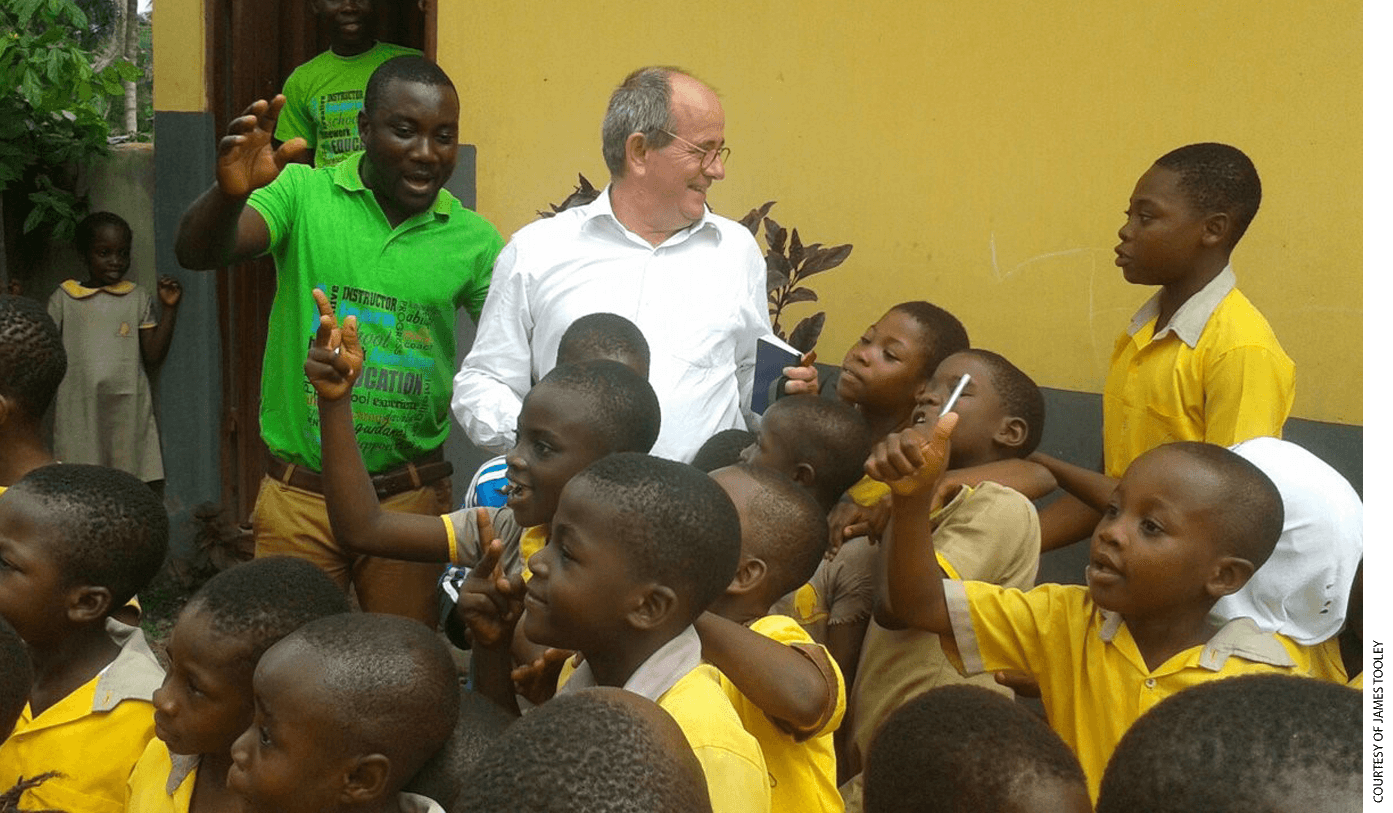

Sixteen years ago, James Tooley, a professor at the University of Buckingham and the former director of the E. G. West Centre at Newcastle, wrote an essay that in 2009 became a pathbreaking book, The Beautiful Tree, which awoke the world to the reality of low-cost but effective private schools thriving in some of the poorest slums of the developing world. Many such schools, Tooley revealed, were outperforming expensive but inefficient state-run schools. So original was the work that Education Next saw fit to use its most telling episodes as the cover story for its Fall 2005 issue. The essay even won a prize, as Tooley is wont to remind us.

Tooley’s Tree has been sturdy enough to weather stern criticism from state school defenders, international organizations, and Nobel Prize winners. Now, Tooley offers an extended reply.

Tooley is not a trained econometrician, and his methods are vulnerable to attack. His landscapes are drawn from personal observations, firsthand accounts, and participant testimonials, not the systematic surveys, quasi-experimental studies, and randomized field trials that mark most contemporary education research. The current book builds on prior research by introducing new entrepreneurial leaders who teach the children of the poor at a very low cost. Tooley’s tales are of interest at a time when affluent parents in

rich countries are forming their own “learning pods” to replace the suddenly closed public schools during the coronavirus pandemic.

It isn’t clear who the intended audience is for this book. Is Tooley still appealing to parents? Or is he now addressing the academic community by taking on critics and broadening his claims? Unclear as to his objective, the author wanders into dense thickets of controversy. Still, he offers up nuggets of gem-like quality.

The largest pearl is a critique of the world’s biggest and most convincing school voucher experiment in Andhra Pradesh, an Indian state with a population of 50 million. To appreciate Tooley’s critique of this study by Karthik Muralidharan and Venkatesh Sundararaman, one must first consider the original accomplishment. With the cooperation of the state government, and supported by funds from the World Bank, the two scholars drew a sample of 360 rural villages. Half of the villages were randomly assigned to receive vouchers, while the other half did business as usual. In the voucher villages, a random half of the sampled children attending state-operated schools were offered vouchers to attend private schools. The study could thus estimate the effects of being offered a voucher or not receiving that opportunity. It could also estimate the effects on all children in a voucher village as compared to those not living in a voucher village. Tracking students two to four years later, the researchers found little difference between those receiving vouchers and those who did not—or between voucher villages and the others. Learning in math, language of instruction, science, and social studies remained the same. The only advantage of receiving a voucher was that a child learned more Hindi, because the subject was only taught in the private sector. As the Times of India put it: “The findings dispel a popular myth that private schools lead to better learning.”

Tooley found the study “disheartening.” His only “comfort” was that the “private schools were on average doing the same for less than one-third the cost.”

One cannot dismiss the study on the grounds that the researchers were fervent supporters of state-run schools, for they themselves had identified extreme inefficiency, if not corruption, in India’s state schools, and the non-ideological quality of their other work suggests they are the kind of scholars who call it as they see it. The study was published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, one of the profession’s most prestigious journals.

But Tooley noticed a detail overlooked by others: the tests were administered in the language officially declared to be the medium of instruction at the school. For the state schools, that language was Telugu, the native tongue of Andhra Pradesh. Among the private schools, about half advertised themselves as teaching in Telugu, while the other half said they taught in English. It might seem to make sense that the research team would administer tests in a school’s language of instruction, but Tooley points out that many of the private schools that report English as the language of instruction are expressing an aspiration more than a practice. While they may teach in English to older students, they conduct much of their instruction in the native tongue. In other words, the students in private schools who took the tests in English were being examined in their second language while the state-school students were being tested in their native tongue. Tooley says the appropriate way of comparing student performance in the two sectors would have been to administer tests to all students in both languages simultaneously. And, in fact, the original study reports that students attending Telugu-language private schools do better than those at state schools, a finding interpreted in the initial investigation as showing that students do less well if they change to a school where the language of instruction is not the same. Perhaps, but the more likely explanation is Tooley’s: Students perform better on tests administered in their native tongue.

After this triumph, Tooley takes on a consensus document from the the Department for International Development, the British agency responsible for foreign aid. Prepared by a group of scholars, the document reported “evidence . . . of inequality of access for girls to private schools,” citing specifically a Tanzanian study that found fewer girls than boys in mixed-gender schools. The consensus document fails to note that many girls attend single-gender schools instead. Overall, 77 percent of the students recruited into private schools are female. This is just one of multiple instances of the department going off in its own misguided direction.

Nor do the Nobel Prize–winning economists Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo escape Tooley’s sharp knives. Admittedly, Banerjee and Duflo, in their book Poor Economics, find that “children in private school learn more than children in public schools.” But Tooley also quotes them as saying private schools are not “as efficient as they could be” or as effective as state schools might be if they were not inefficient, corrupt, and focused on inappropriate goals. In other words, Banerjee and Duflo are judging private schools against an ideal standard rather than currently available alternatives.

Tooley’s warm stories of entrepreneurial accomplishments and cutting critiques of other research both appear in the early chapters that comprise Part I. He might well have ended the book there, for the rest of the volume loses focus. Part II offers a rambling critique of government-operated schools, with a focus on the wayward policies of Tooley’s home country. In Part III he takes on education reform across the pond. Tooley does not like charter schools, nor does he think much of vouchers. Forgetting his critique of Banerjee and Duflo for criticizing the real from some ideal standpoint, Tooley says choice interventions in the United States fall short of the libertarian economist E. G. West’s vision of totally privatized schooling. For Tooley, the pandemic cannot last too long if it drives everyone to pod learning—even if the teachers managing the pods are poorly paid.

No one can accuse Tooley of iterating conventional wisdom. The Beautiful Tree proves that. But as Really Good Schools goes on and on, the author strays farther and farther from his main turf into lands better left untraveled.

Paul E. Peterson is the Henry Lee Shattuck professor of government at Harvard University, director of Harvard’s Program on Education Policy and Governance, and senior editor of Education Next.

The post To Critics of The Beautiful Tree, a Pearl of a Reply appeared first on Education Next.

By: Paul E. Peterson

Title: To Critics of The Beautiful Tree, a Pearl of a Reply

Sourced From: www.educationnext.org/to-critics-of-the-beautiful-tree-pearl-of-reply-review-really-good-schools-tooley/

Published Date: Wed, 03 Mar 2021 10:00:40 +0000

News…. browse around here